Elements of a counter‐exhibition: Excavating and countering a Canadian history and legacy of eugenics

news, new scholarship & more from around the world

A saloon in the Devil’s Half Acre

History of the Human Sciences, Ahead of Print.

The Caraka Saṃhitā (ca. first century BCE–third century CE), the first classical Indian medical compendium, covers a wide variety of pharmacological and therapeutic treatment, while also sketching out a philosophical anthropology of the human subject who is the patient of the physicians for whom this text was composed. In this article, I outline some of the relevant aspects of this anthropology – in particular, its understanding of ‘mind’ and other elements that constitute the subject – before exploring two ways in which it approaches ‘psychiatric’ disorder: one as ‘mental illness’ (mānasa-roga), the other as ‘madness’ (unmāda). I focus on two aspects of this approach. One concerns the moral relationship between the virtuous and the well life, or the moral and the medical dimensions of a patient’s subjectivity. The other is about the phenomenological relationship between the patient and the ecology within which the patient’s disturbance occurs. The aetiology of and responses to such disturbances helps us think more carefully about the very contours of subjectivity, about who we are and how we should understand ourselves. I locate this interpretation within a larger programme on the interpretation of the whole human being, which I have elsewhere called ‘ecological phenomenology’.

The new edited volume, Voices in the History of Madness: Personal and Professional Perspectives on Mental Health and Illness, may interest AHP readers. Edited by Robert Ellis, Sarah Kendal, and Steven J. Taylor, the book is described as follows: This book presents new perspectives on the multiplicity of voices in the histories of mental ill-health. … Continue reading Voices in the History of Madness: Personal and Professional Perspectives on Mental Health and Illness →

A new piece in Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne by Jennifer Bazar and Christopher Green will interest AHP readers: “How Canada’s first psychology department arose at McGill University.” Abstract: Canada’s first official department of psychology came into existence at Montréal’s McGill University in 1924. First chartered more than a century before, in 1821, McGill started teaching courses … Continue reading How Canada’s first psychology department arose at McGill University →

Richard M Titmuss (1960)

One reason why the Rand researchers knew their findings might be controversial was the reaction to an audacious and for the time methodologically advanced experiment conducted by husband and wife team of Drs. Mark and Linda Sobell (above), results from which had been published in 1973.

Firefighters tackling the blaze at the Triangle Shirtwaist factory, New York City, March 25, 1911

Benjamin Rush’s twin 1786 letters on the different species of phobia and mania sit at an extended historical juncture at which an early modern quasi-medical troping of mental disorder in American social commentary sobered up to mental medicine. The letters’ satirical drive hinged on a perennial problem still occupying George Beard almost a century onward: which idiosyncratic trepidation or ill-grounded idea warranted the nomination of national and epochal ill? Rush’s mania letter exemplified an established genre identifying popular and especially political crazes; at the same time, it foreshadowed the early 19th-century rise and mid-century fall of monomania as forensic-nosological stopgap. The phobia text established the term’s dictionary (OED) sense of specific morbid fears, but did so in the form of a mobilisation of nosological jargon for social diagnostics purposes: an ambivalent prelude to Rush’s later formal engagement with unreasonable fears and follies. Both letters draw attention to a pervasive duality in early modern and Enlightenment conceptions of hydrophobia, aerophobia, syphilophobia and lyssophobia, between public-health and mental-hygienic follies.

Working-class delinquent girls who were thought to be in need of long-term ‘reeducation’ could end up in the Dutch State Reform School for Girls. In the 1930s and 1940s girls were assessed by means of the Rorschach inkblot test after they were admitted. This psychological test, for which they had to tell the institutional psychologist what they saw in ten inkblot cards, served to assess how difficult or easy they would make life for the staff, and functioned to get them to behave well. It did so by creating the idea that the psychologist could look inside the girls, which forced them to look inside and wonder what it was that the psychologist could see.

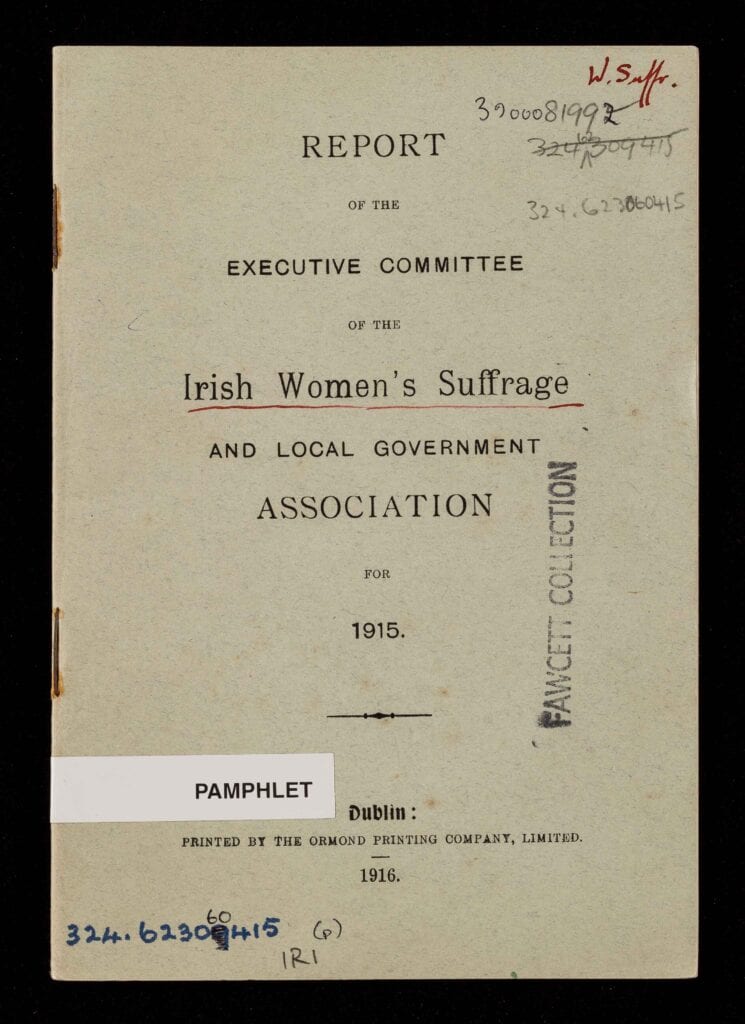

Scholar of social work Viviene Cree examines “khaki fever” and a surprising response among women who decided they had to stop it.

This article will demonstrate the significant influence that psychiatric consultants exerted on the policy of the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) and, as a result, on cinematic representations of mental illness and psychiatric practices during what Arthur Marwick (2005) called the ‘long 1960s’.