No, but here’s what we learned.

Writing a will can improve the transmission of wealth across generations, by preventing the dissipation of assets such as a family home when divided among multiple heirs. But by age 70, only 67 percent of households have a will, and that share is much lower for less wealthy households and for Black and Hispanic households. The question is whether targeted bequests can be increased through an intervention that promotes will-writing.

To answer that question, we undertook an online survey administered by NORC at the University of Chicago. The participants were first asked a series of questions about whether or not they have a will and why. Then, those without a will participated in an experiment where they were randomly assigned to either a control group or one of three treatment groups to determine whether various incentives would encourage them to write a will.

Control Group: Do you intend to write a will?

Treatment Group 1: If the bank offered the opportunity to establish a will (with free legal and financial advice) at the time of signing for the mortgage, would you take up that offer?

Treatment Group 2: If the bank offered the opportunity to establish a will (with free legal and financial advice) at the time of signing for the mortgage and gave you a $500 incentive to do so, would you take up that offer?

Treatment Group 3: Imagine you are opening a checking, savings, or investment account at a bank. If the bank offered the opportunity to establish a will (with free legal and financial advice) when you opened the account, would you take up that offer?

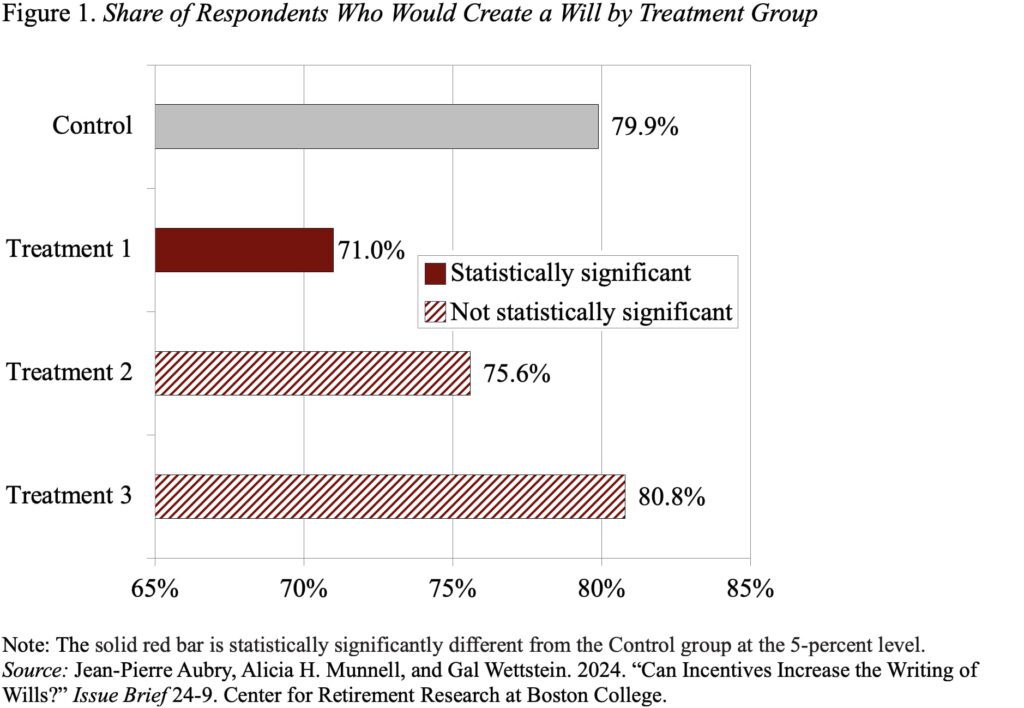

The disappointing news is that the first two treatments, which associated will-writing with the taking out of a mortgage, actually reduced the percentage of respondents who said they intended to write a will (see Figure 1). Without any treatment, 79.9 percent reported they intended to write a will; once the question was linked to the mortgage process, the percentage dropped to 71.0 percent – even with the offer of “free legal and financial advice.” Adding $500 to the proposal only brought the percentage halfway back to the no-treatment level. When the scenario changed from a mortgage environment to simply opening a bank account, the percentage intending to write a will increased to 80.8 percent.

For a number of reasons, the best way forward was to drop the control group and compare

the treatment groups among themselves. The results of this exercise show that offering $500 has barely any effect, but – even without the financial incentive – simply changing the base event from taking out a mortgage to opening an account increases the share intending to write a will by a lot. We also used this formulation of the experiment – comparing the treatment groups among themselves – to assess the impact of treatments by individual characteristics.

The bottom line from these results is threefold.

- Most importantly, the setting matters. Trying to combine a somewhat complicated and emotional task such as writing a will with a complicated and exhausting process like taking out a mortgage does not work.

- Money – in this case, $500 – increases the percentage of some individuals willing to write a will, but the effect is only half that associated with changing the setting.

- Finally, the impact depends on the characteristics of the individuals. The more financially sophisticated tend to react somewhat differently than the unsophisticated. The impact also varies by race; albeit not by gender.

So, in the end, even disappointing results can provide some real information.