If Andrew Biggs and I can agree, the shift should have bipartisan support.

Andrew Biggs, a conservative economist with the American Enterprise Institute, and I are usually opponents. Our disagreements go back decades – privatizing Social Security, adequacy of retirement income, compensation of state and local government employees – and just a few weeks ago I thought he was really off base arguing that workers do not pay for their Social Security benefits.

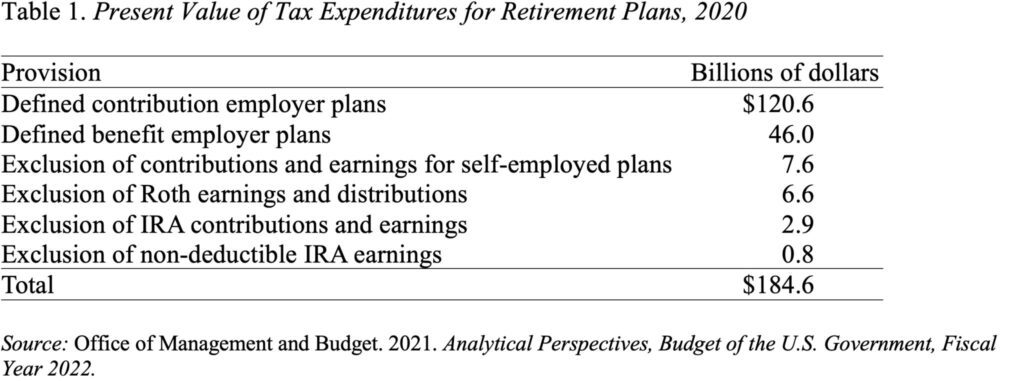

Sometimes, however, we see things the same way. We both have concluded that: 1) the subsidies for private sector retirement plans do little to increase private saving; and 2) the revenues raised from repealing these “tax expenditures” could be better used to address Social Security’s funding gap. The tax expenditures, under the personal income tax, arise because employees can defer taxes on compensation that they receive in the form of retirement savings. This tax treatment significantly reduces the lifetime taxes of participating employees, relative to saving through an ordinary investment account. It also cost the government $185 billion in 2020, equal to about 0.9 percent of GDP.

Who gets the tax expenditure? Studies show that 59 percent of the current tax expenditures for retirement saving flows to the top quintile of the income distribution. This pattern is not surprising, given that upper-income taxpayers are more likely to have access to employer-sponsored retirement plans, are more likely to participate in their employer’s plan, and contribute more when they do participate.

And recent changes will increase the share going to the top quintile. Expanded “catch-up” contributions benefit only those constrained by the existing limits – roughly 16 percent of participants. And increasing the age to 75 for taking required minimum distributions allows participants to take advantage of 4½ more years of tax-free growth. Generally, only the wealthiest will be able to benefit from this provision.

What do the tax expenditures buy us? Given that the tax expenditures go overwhelmingly to upper-income households, who face almost no risk of poverty in old age, it is important to ask whether these expenditures accomplish some broader social goal, such as increasing national saving.

Theory does not provide a strong basis for assuming that the federal tax preferences increase total saving. Yes, tax preferences make retirement saving more attractive and massive amounts have been accumulated in retirement plans. But the economists’ lifecycle model suggests that people may simply shift savings from ordinary taxable investment accounts to tax-favored retirement accounts.

Indeed, the evidence supports the predictions of the lifecycle model. The definitive 2014 study, using Danish tax data, looked at responses to a reduction in the subsidy for retirement contributions for those in the top tax bracket. The results show that, for some, pension contributions declined. But the decline was nearly entirely offset by an increase in other types of saving. The tax subsidy, in other words, had primarily induced individuals to shift their saving from taxable to tax-advantaged retirement accounts, not to increase overall household saving.

Given that the tax expenditure for retirement plans is a bad deal for taxpayers, it makes sense to curtail these tax breaks and reallocate the proceeds. Over the next 75 years, Social Security faces an actuarial deficit of 1.3 percent of GDP, so applying the revenues from eliminating the tax expenditure would solve 70 percent of the problem. And the gains would be higher than this estimate for two reasons: 1) the government would continue to collect income taxes on past tax-preferred contributions; and 2) payroll tax revenues would be higher as well because they are also affected by the tax preferences.

In short, let’s move government resources from retirement plans where the incentive does virtually nothing for retirement security to a program that indisputably does – Social Security.